A federal agent has testified that Georgia labor officials were bribed by an alleged criminal organization accused of subjecting farmworkers to forced labor and degrading living conditions, including housing dozens in a single-room trailer without safe drinking or cooking water.

In sworn testimony, the Homeland Security Investigations special agent said the bribery was related to farmworker housing inspections. Passing the inspections can be a key requirement of federal approval to bring seasonal farmworkers to the U.S. on temporary visas.

The special agent provided the previously unreported testimony during a sentencing hearing linked to Operation Blooming Onion, one of the largest federal cases ever prosecuted in the U.S. involving labor trafficking of guest farmworkers. So far, the investigation has led to criminal prosecutions against 28 defendants charged with forced labor conspiracy or other crimes.

In the March 30 hearing, U.S. Assistant Attorney Tania D. Groover asked agent Julio Lopez if the organization targeted by Blooming Onion was bribing public officials.

“Were they also bribing state work employees of the Georgia state Department of Labor to approve housing for H-2A workers?” Groover asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” Lopez answered.

Bribery wasn’t mentioned again in the hearing.

It appears that no current or former Georgia labor employees have been charged with bribery in the case based on the list of defendants identified by Barry L. Paschal, spokesman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of Georgia.

Paschal declined to comment, saying the office can’t discuss active investigations. Lindsay Williams, a spokesman for Immigration and U.S. Customs Enforcement did not make Lopez available for an interview or respond to questions related to his testimony.

Kersha Cartwright, spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Labor, said the agency was not aware of the testimony about bribes until a USA TODAY Network reporter asked about it. She noted that the agent’s statement is very broad and provides no evidence or specifics.

Asked whether the department would discuss the allegations with employees who perform the housing inspections, Cartwright said: “What do you want us to ask? ‘Did y’all take bribes?’”

She said the Human Resources Department will follow up but said she couldn’t speak as to the measures they would take.

Andrew Walchuk, senior policy counsel and director of Government Relations for the advocacy group Farmworker Justice, said that the Georgia Department of Labor should prioritize investigating the allegations.

“It’s really horrifying to imagine that state officials who are responsible to look out for those workers’ health, responsible to make sure that the law is complied with,” he said, “would instead take money, allegedly, from the employers who allow these workers to suffer abuse and allow these workers to live in really terrible conditions.”

The special agent’s testimony reveals yet another potential connection between the Georgia Department of Labor and the Blooming Onion case. In April, the USA TODAY Network exposed links to two Georgia Department of Labor officials – one then current, the other former – who had been charged with protecting migrant farmworkers.

The then-current employee, Jorge Gomez, was tasked with advocating for migrant farmworkers as the state monitor advocate.

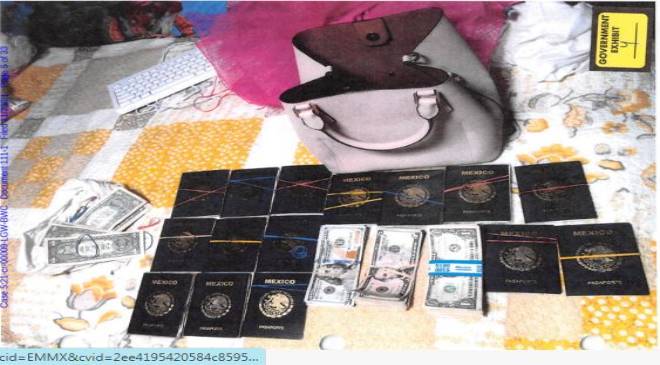

The USA TODAY Network reported that officers had searched Gomez’s home during the investigation and that one of his sisters and a nephew were indicted in the largest case tied to it. Federal authorities confiscated money from his daughter, who lived with him and helped employers get approval to bring in guest farmworkers. At least 10 of Gomez’s relatives had business ties to employers of seasonal workers.

Neither Gomez nor his daughter have been accused of any wrongdoing. Within two weeks of the story’s publication, Gomez, then 59, applied for disability retirement and has since retired.

Citing the story, advocacy groups now are calling for the U.S. Department of Labor to include clear conflict of interest standards for all state monitor advocates.

“We should not be in these situations where the individual who is responsible to protect the interests of farmworkers is so closely tied to the interests of the employers,” Walchuk said.

Gomez has not answered phone calls, texts or an email with questions about his retirement or the testimony concerning bribes.

Before retiring, he performed housing inspections and told USA TODAY that he provided technical assistance to other Labor Department employees doing them. He also said that he recused himself from tasks and decisions that affected his family members’ clients.

Responding to an allegation from the husband of an agent who prepares guest farmworker petitions, he said he had never charged money to do inspections.

‘Degrading living conditions’

Employers who hire guest farmworkers are required to provide them with free housing and tell state and federal agencies where they will be living. In many cases, the Georgia Labor Department must inspect it to ensure it complies with federal rules, including meeting sanitation and maximum occupancy standards.

Passing the inspection, when one is required, is necessary for employers to get federal authorization to bring in guest farmworkers.

Complaints about guest farmworker housing conditions in Georgia aren’t new. Housing can be a significant expense and some employers try to cut those costs.

For example, a federal labor inspector found that Daniel Mejia, a farmer and contractor operating in Georgia, housed workers in locations he hadn’t disclosed to authorities in 2017. Mejia said the motel where he had told authorities he would house workers was too expensive, so he took them instead to labor camps with trailers, the inspector’s report said.

The inspector said that housing violated standards: an overflowing septic tank, evidence of roaches in the refrigerators, water leaks in the living units and a hole in a wall large enough for animals to crawl through.

Mejia, also known as Daniel Perez-Mejia, told the USA TODAY Network he didn’t remember many details about the housing violations but fixed them after the inspection.

Advocates have long warned that guest farmworkers can be reluctant to speak out about substandard housing or other abuse: if they get fired or quit, they generally lose their visa and sometimes, their best chance to repay debt they may have gotten into to get the U.S. job.

Walchuk, with Farmworker Justice, said the degree of control that employers have over the workers makes it important that the authorities in charge of protecting them do anything in their power to do so.

The largest indictment tied to the Blooming Onion investigation, which charged two dozen people with conspiring to engage in forced labor and related crimes, said defendants required workers to pay illegal fees to obtain jobs, made them work for little or no pay and threatened them.

It also says conspirators required foreign workers to live in “crowded, unsanitary, and degrading living conditions.” Some of the workers, the indictment said, were forced to live with dozens of other employees “in a single room trailer with little or no food and limited plumbing and without safe drinking or cooking water.”

Other workers were housed in a “hazardous trailer” and in “cramped, dirty trailers with raw sewage leaking into the trailers,” the indictment said.

It’s unclear whether that housing was inspected by the Georgia Department of Labor.

The indictment doesn’t identify where the housing was located or whether those locations had been disclosed to authorities. In addition, federal regulations generally don’t require state labor inspections when workers are housed in public accom

The defendants who entered pleas in that case have pleaded not guilty. Javier Sanchez Mendoza, during whose sentencing hearing the federal agent testified about bribes, pleaded guilty to forced labor conspiracy but is appealing his case. Two other defendants have pleaded guilty to forced labor or mail fraud conspiracy in separate cases. A fifth case is ongoing.

Among those who have pleaded not guilty in the largest case is Brett Bussey, the other former Georgia Labor Department employee with links to the investigation. Bussey used to inspect guest farmworker housing before leaving his government job in 2018 to work as an agent helping businesses prepare petitions to bring guest farmworkers. He was indicted with conspiracy to engage in forced labor and other related crimes. .

U.S. Department of Labor spokeswoman Monica C. Vereen said that the department is taking the allegations of bribery very seriously and is reviewing them. The agency funds state activities related to the processing of guest-worker petitions, including housing inspections.

Chris Butts, executive vice president of the Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Association, said the proper authorities should investigate any credible allegations of wrongdoing to protect both the workers and the guest farmworker program which, he said, is critical to the association’s growers. If the allegations are true, he said, people should be punished.

“Any time that you have bad actors,” he said, “that puts the program at risk.”