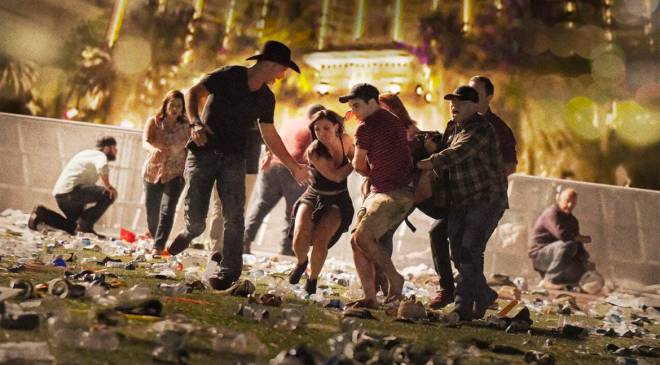

In terms of unadulterated experiential terror, 11 Minutes has few non-fiction equals, utilizing an array of cellphone and bodycam videos to place viewers directly in the midst of the mass shooting at Las Vegas’ Route 91 Harvest country music festival on Oct. 1, 2017. Fifty-eight people died that evening and another 869 were injured, all due to the lethal actions of a lone gunman firing from a room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay hotel. Boasting commentary from Jason Aldean, who was on stage as the event headliner when the madness erupted, director Jeff Zimbalist’s four-part docuseries (Sept. 27, Paramount+) immerses itself in the moment-to-moment chaos of that calamity with stunning urgency. It’s a long-form portrait of hell that, figuratively speaking, never ends, both in its victims’ minds and in America, where massacres like this are now somehow accepted as par for the course.

11 Minutes makes an issue out of not naming the perpetrator of this heinous atrocity, contending that doing so only leads to glorification and copycats—and, also, that the individuals who truly deserve to be remembered are his innocent victims and the heroes who risked their lives to save as many as possible. Certainly, anyone curious about the man’s identity can find it in a heartbeat online, and since authorities continue to have no comprehensive clue about why he did what he did, there’s not a lot to be gleaned from focusing on him. A far bigger omission, however, is a serious discussion about our never-ending national infatuation with firearms. Except for a fleeting five-minute segment in episode 3 in which the “debate” over guns is presented via TV news clips, and the parents of victim Carrie Parsons argue against assault weapons and discuss their efforts to successfully outlaw bump stocks (which transform semi-automatic guns into fully automatic ones), the series avoids overtly addressing the most easily preventable element of this slaughter.

11 Minutes is frustrating in its refusal to scream—loudly, angrily, hysterically—over the blatant insanity of any person being able to legally purchase over 55 firearms in one year, including the fourteen AR-15 rifles, eight AR-10-type rifles, and single bolt-action rifle and revolver that were found in the shooter’s Mandalay Bay room. Nonetheless, if Zimbalist’s docuseries is deliberately subdued on this most important of points, its on-the-ground footage paints a deafening portrait of the carnage wrought from our status quo. In the sights and sounds of screaming men and women huddling for protection, racing through the venue’s grounds as bullets whiz through the air, hiding behind cars and walls, and frantically carrying the wounded past (and over) the dead to cops and EMTs on the scene, who themselves are taking heavy fire and suffering grave injuries, it affords an up-close-and-personal view of being in the thick of a mass shooting—which, unsurprisingly, feels akin to a war zone.

That material is harrowing, and edited together to provide a clear, chronological, multi-perspective snapshot of how things went down during the attack. Better still, 11 Minutes is driven by the recollections of a wide range of attendees, police officers and medical personnel who endured this horror, much of which is then accompanied by actual video and audio of the stories they’re telling. From twin sisters Gianna and Natalia Baca and the former’s boyfriend Parker Max (whose father was part of the responding SWAT team) striving to make it out alive, to Kelly Pollard, who valiantly tried to get her friend Cassie to safety, Zimbalist presents a collection of heartrending accounts that take one from the stage to the street to nearby Sunrise Hospital, where doctors dealt with an overwhelming influx of critically injured patients, and where the white floors soon became covered in blood.

Of those narratives, the most affecting is that of Jonathan Smith, a Black man who faced discrimination shortly before the shooting (when a guy stated that he was surprised “your kind” liked country music), heroically evacuated people from the area, took a bullet to the chest, and was ultimately rescued by white San Diego police officer Tom McGrath. In his ordeal, 11 Minutes captures the ugly and the inspiring of 21st-century America. Cops race toward danger in order to protect the powerless. Strangers put the welfare of others ahead of their own, at great peril—and with tremendous consequences. And civilians exhibit perseverance, courage and resilience despite unbelievable circumstances—none more so than Natalie Grumet, a breast-cancer survivor whose jaw was shattered by a round from the shooter’s rifle.

As for Aldean, he provides a few remarks about his own experience being ushered into a tour bus, as well as some platitudes about healing through togetherness; more intense is Dee Jay Silver’s tale about discovering that his 1-year-old son was with a nanny on the same 32nd floor as the shooter. Though its outcome is now well-known, 11 Minutes thrums with anxious intensity as it charts concertgoers’ attempts to exit the venue (which was shadowed by the Mandalay Bay, making it a veritable shooting gallery), cops’ struggles to help others as well as their own, and everyone trying to make sense of the senseless. Meanwhile, CCTV snippets of the shooter arriving at the hotel and spending time playing video poker (which was apparently his primary profession) provide a haunting calm-before-the-storm counterpoint to the pandemonium he instigated, all for reasons that are as mysterious now as they were then.

11 Minutes’ value lies in its immediacy, which underscores the nightmarishness begat by our unwillingness to put systems in place to keep military-grade weapons out of civilians’ hands. Still, director Zimbalist’s decision to focus on you-are-there anarchy—and, by extension, to let his material do the talking—also comes across as a bit of an evasion. In the face of such calamitous monstrousness, the docuseries’ disinterest in more vocally confronting the source of this avertible suffering does a disservice to those who lost their lives that day, and to all the others who, as its in memoriam coda makes clear, died in the numerous similar tragedies that have followed in its wake.