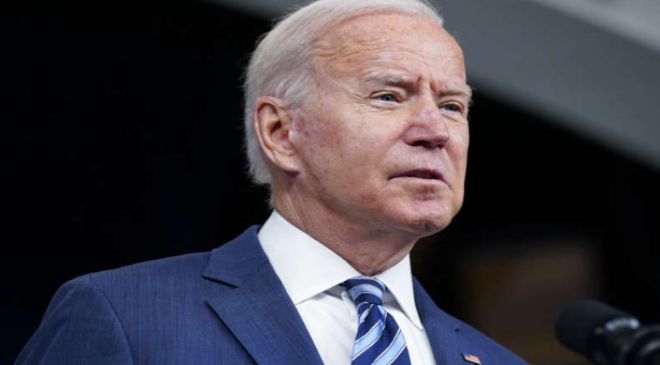

One year ago, President Joe Biden stood in front of a U.S. Capitol that still bore the wounds of an insurrectionist siege, taking the oath of office at a time when the nation faced its greatest array of crises in nearly a century.

He pledged that day to prove that the nation’s very democracy still worked, that he could restore unity to a divided country, tame a killer pandemic and steady a shaky economy. In the 12 months that have followed, unemployment has been slashed, a pair of transformative spending bills have been passed and life-saving vaccines were made available to nearly all Americans.

For all that, however, the president ends his first year undeniably weaker than he began it, with his poll numbers having plummeted and his party in danger of being swept out of power on Capitol Hill. His team insists they aren’t thrown by their turn of fortune and that history will be on their side.

“It does not surprise me that despite progress on Covid, despite progress on the economy, voters are not going to give us a passing grade yet,” White House chief of staff Ron Klain said in an interview. “But President Biden was elected to a four-year term, not a one-year term.”

Biden’s first year in office was almost evenly bifurcated between success and struggle.

In his first six months, he successfully steered a $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief bill to passage, surging funds to American families, schools and businesses battered by the pandemic. His administration rolled out a massive vaccine distribution program that made the protective shots available to every American just months after they were approved for use. He unveiled a series of economic policies that, by the end of his first year in office, would help cut unemployment from nearly 9 percent on Inauguration Day to 3.9 percent now.

Biden declared that America could have faith in its government again, as he sought to turn down the temperature in a Washington overheated by his predecessor, Donald Trump.

But in the late summer, the Biden administration was dramatically derailed, thrown off course by both unanticipated events and political missteps of their own making.

Only weeks after Biden used July 4 to declare America’s independence from the Covid virus, the lethal and highly transmissible Delta variant deluged the nation, preying largely on the unvaccinated to send death totals and hospitalizations soaring. Then the world watched in horror as the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan was filled with images of tumult and violence.

The administration tried to pitch each development as a testament of their mettle—they’d ended the nation’s longest war and were confronting the virus. But for a president that had made competency central to his message to the American public, the pair of missteps was politically damaging. His poll numbers have yet to recover.

In late November, reports emerged from South Africa about another new, even more highly transmissible Covid variant. As the holidays came, Omicron brought much of the nation to a halt, forcing Biden to end the year facing a new round of questions about his ability to handle the job.

“It’s the best of times, it’s the worst of times. You can divide his year pretty evenly, with the president starting by doing some important things to get the country back on track,” said Robert Gibbs, former press secretary to President Barack Obama. “But what started in August with Afghanistan, to me, is that since then this is a White House that has been shaped by external events, it isn’t doing the shaping of those events.”

Winning the White House on his third try, Biden took the helm of a nation worn down by the pandemic, which had claimed hundreds of thousands of American lives and reshaped the norms of everyday life. Trump’s combative term ended with a refusal to accept the results of the election, his torrent of lies igniting a deadly riot at the nation’s Capitol.

Biden was meant to be a steadying hand, a president welcomed in part for simply not being his predecessor. But citing the pandemic and the insurrection, Biden and his aides believed they needed to go big out of the gate. The president and his team invited comparisons to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “New Deal” and Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society.”

A party-line vote turned the Covid relief bill into law. And Biden managed to secure an elusive bipartisan win with the passage of a $1 trillion infrastructure package this fall that is poised to be a godsend to the nation’s decaying roads, bridges and water pipes.

But the legislative process has been marked by intense Democratic infighting and the failure to move the rest of Biden’s Build Back Better agenda. Increasingly, the president’s ambition felt more like an overreach, out of step with the Democrats’ slim margins in Congress. Biden made repeated, personal attempts to move the Senate’s two centrist Democrats, Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.). There were some breakthroughs. But on the big ticket items, including voting rights, there has not been success. It has left Biden appearing, at times, as president of the Senate rather than the nation as a whole, as his administration became bogged down in the legislative morass. Republicans, with few exceptions, were eager to play obstructionists and polling suggested a nation nervous about inflation also wanted Biden to scale back.

“They misread their mandate,” said Alice Stewart, a Republican strategist and veteran of several GOP presidential campaigns. “Their mandate was to unify the country and put an end to Covid. But he has been persuaded by the left to try to enact transformational change and social spending and election reform that the public does not want.”

The White House has made no apologies for the scale of its agenda.

“The president became president at a time of great crises in the country. A Covid crisis, an economic crisis. The voters didn’t say ‘Go do a little bit,’” said Klain. “We put forward three key proposals: Covid relief, infrastructure, and Build Back Better. We had a bold agenda and achieved two of the three.”

The challenge, Klain continued, “is not that we have tried to do too much, but that we have more to do.”

For as shaky as the end of Year One was, the White House sees reasons for optimism as Biden begins his second in office. Though voting rights legislation seems stalled, the Build Back Better spending agenda could be revived, albeit a scaled back version. There are signs that the Omicron variant, less deadly than Delta, has peaked in parts of the country it first hit. And some economists believe that inflation will ease before voters head to the polls for November’s midterm elections.

Some Democrats take comfort in the knowledge that their party’s last two presidents — Obama and Bill Clinton — each struggled their first year only to win reelection. But historic trends and current polling both favor Republicans this November, and Trump has begun a return to the political stage, fueling talk of a 2024 comeback.

“He has some big accomplishments but his agenda seems to have no path forward and inflation really looms as a problem for the country,” said Julian Zelizer, presidential historian at Princeton University. “It is certainly not a stalled presidency, but he starts the new year with lots of trouble.”