On bad days, when Jeff Jordan has gone to bed to the thrum of power plant turbines or awakened to the stench of asphalt production, he worries that his hometown is doomed to die.

Jordan, 62, has lived all his life in Randolph, Arizona, an unincorporated and economically depressed community 60 miles southeast of Phoenix that was founded a century ago by Black migrant farmworkers. Over the past three decades, as polluting industries have encircled Randolph, the population has shrunk and feelings of dread and frustration have taken hold.

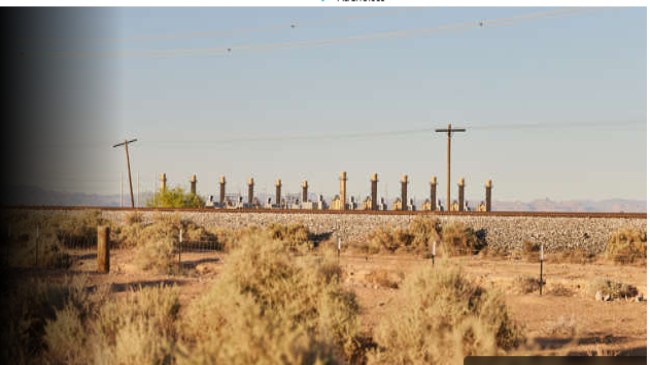

Jordan fears the final blow may come from a local utility’s plan to more than double the size of its power plant. The Coolidge Generating Station sits on the other side of Randolph’s eastern border, its 12 turbine engines burning natural gas for electricity, a process that emits carbon dioxide.

The project — which would join several expansions of natural gas-burning power plants in development around the country — is being pushed by the Salt River Project, a nonprofit utility, as a way to meet a surge in power demand in the Phoenix region. The nearby city of Coolidge, which stands to reap millions in tax revenue, has endorsed the project. On Tuesday, the Arizona Corporation Commission will vote on whether to approve it.

Environmentalists are challenging the proposal, saying adding fossil fuel-burning facilities would undermine efforts to curtail greenhouse gases warming the planet. The people of Randolph, many of whom see the expansion as part of a long pattern of environmental racism by the government and industry, worry about the effects of added air, light and noise pollution — and the fate of their community.

“It impacts people’s hearts, and they don’t want to be around this,” Jordan said recently by phone from his home on the southern end of Randolph, part of the property where he and 11 siblings were raised. “It’s kind of like they’ve oppressed us for so long that people here are almost out of gas. They don’t have the fight anymore, so they just get up and leave.”

The proposed power plant expansion embodies the tensions of America’s rocky shift from fossil fuels to renewables, a move scientists warn must be made quickly to curb global warming enough to avoid climate disaster. Utilities say they cannot make the switch without using natural gas as a “transition” fuel as they turn away from coal and produce more energy from wind and solar. But climate change scientists say that argument is no longer valid with the world running out of time.

Caught in the middle are communities like Randolph.

Jordan’s grandfather was one of Randolph’s earliest residents. He remains close with many of the community’s old-timers. That is why, instead of following other former residents to bigger towns elsewhere, he has chosen to stay and fight.

“This is my home,” Jordan said. “This is where I grew up. This is my heritage. This is who I am.”

Growing industry, shrinking community

Jordan’s grandfather moved to Randolph from Arkansas as part of an early wave of Black farmworkers seeking jobs in the area’s cotton fields in the early 1940s. His son — Jordan’s father — followed and met Jordan’s mother, a member of the Gila River Indian Community, while picking cotton.

In those early years, Randolph was a destination for Black people who wanted to buy their own property. Historians estimate that at its height, Randolph was home to 500 people, a post office and some stores. Today those amenities are gone, and about 150 residents remain.

Jordan attributes Randolph’s decline to the influx of industry that began when he was in his 20s. As a community without a municipal government or a school district — its students attend school in Coolidge, about 5 miles away, and its only local elected leader is a Pinal County supervisor whose district includes Randolph — the people of Randolph do not have much of a political voice to influence development at their borders.

The surrounding land includes the Coolidge Generating Station, an asphalt emulsion plant and a bridge parts factory. A Union Pacific freight line runs along Randolph’s eastern edge, not far from the scene of a February derailment that spilled cyclohexanone, a toxic chemical, but did not result in any reported injuries. Also nearby is the El Paso Natural Gas pipeline, a section of which ruptured and exploded in August, killing a man and his daughter living in a farmhouse on the outskirts of Coolidge.

In August, Randolph property owners began getting letters from the Salt River Project announcing its intentions to add 16 gas-powered turbines to the Coolidge Generating Station. The expansion, which would be completed in 2024 and 2025, is crucial to meet a soaring increase in energy demands in one of the fastest-growing regions of the country, the utility says. The plant’s new capacity would be used during times of peak power needs, the utility says.

While the Salt River Project says it is closing coal plants and expanding its renewable energy production, it says there is no way it can meet immediate spikes in demand or its long-term carbon reduction pledges without also adding gas-burning generation. Using solar and battery storage to meet the same goals would be too expensive and would not be as dependable, Salt River Project executives said in an interview.

The Coolidge expansion “would give us time to adopt renewables at a measured pace and help us make that transition in a reliable way,” said Grant Smedley, the director of resource planning at the Salt River Project.

Other utilities around the country are making similar arguments for new gas-burning plants. Climate scientists say it is a mistake.

“We should be going all out on renewables for the sake of the climate, public health, energy security, etc., and none of those are consistent with construction of new gas fired power plants,” Drew Shindell, a professor of earth science at Duke University and an author of a 2018 report on global warming by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, wrote in an email.

In Arizona, the state Sierra Club chapter says the Salt River Project is trying to rush its plan through the approval process by not seeking bids from greener developers.

“To me this demonstrates that they’re just not taking climate change seriously enough,” said Sandy Bahr, the director of the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter, which formally opposed the Salt River Project’s request before the Arizona Corporation Commission.

If the commission’s five elected members approve the expansion, the Salt River Project will need to get an air quality permit from Pinal County before it starts construction.

Three members of the commission declined to comment, saying they did not want to speak before the vote Tuesday. The two others did not reply to messages seeking comment.

‘The system has failed us’

Randolph residents opposed to the project, including Jordan’s oldest brother, Ron, who owns part of the old family homestead, hired a lawyer and have gotten involved in the case, as well.

In public hearings and legal filings, the residents have placed the project in a long history of governmental neglect and discrimination, starting with its founding by Black people who were not allowed to buy property in nearby Coolidge. The plant and the light, noise and particulate matter it emits would worsen surrounding industries’ effect on residents’ health, property values and enjoyment of the outdoors, they said. It would also hasten the demise of an important piece of Arizona history, they said.

“What we see here, as we have seen many times before, is a powerful entity destroying what Black communities have built,” the residents argued in a brief to the commission last month.

The Salt River Project, which bought the plant from a Canadian company in 2019, does not dispute that the people of Randolph have been treated unfairly. But its expansion project “is neither a cause nor contributor to that past mistreatment,” the utility said in a brief to the commission last month. The project’s environmental effects on the community “will be minimal,” the utility wrote.

The city of Coolidge supports the project, citing potential economic benefits, including $10 million in additional property tax revenue from 2024 to 2033 and $31 million more in property taxes for the school district.

City Manager Rick Miller said that Coolidge is concerned about neighboring Randolph and that a new committee of government and utility officials and Randolph residents is seeking ways to improve the community. “We’re not insensitive to their feelings,” Miller said. “They are our friends.”

So far, the utility has promised to contribute community improvements to Randolph that it valued at $10.5 million to $13.3 million. The plan includes dimming nighttime lighting, paving roads to reduce dust, erecting landscaping screens around the plant, paying for job training programs and scholarships and helping the community get designated as a historic site.

“We think we can play a significant role in helping that community and respond to larger concerns they’re experiencing,” said Rob Taylor, the Salt River Project’s chief public affairs executive.

To many in Randolph, Jordan included, those promises are too late.

“I feel that the system has failed us,” Jordan said. “Our experience has shown that. Particularly for economically disadvantaged people, particularly for people of color.”

But Jordan, a Pima Indian who works as a project manager for the Gila River Indian Community, said he feels an obligation to his neighbors and ancestors to keep pushing.

He and about 30 other Randolph residents plan to attend the commission’s hearing Tuesday to oppose the project, he said.

“I hope they will do the right thing,” Jordan said. “It doesn’t look promising.”