President Joe Biden issued an urgent and ominous warning to American individuals and businesses Monday, when he said “evolving intelligence” suggests Russia might be planning cyberattacks against the US.

On Tuesday, an FBI advisory was sent to US companies in the energy, defense and financial sectors, warning of potential prep work for hacking from IP addresses in Russia.

This activity is likely “not about espionage, it’s probably very likely about disruptive or destructive (cyber) activity,” US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Director Jen Easterly said during a phone briefing with industry executives and state and local government personnel, according to three sources on the call, writes CNN’s Sean Lyngaas.

Many warnings of a looming Russian cyberattack

The advisory is part of a growing chorus of warnings that US infrastructure is at risk, writes Lyngass.

“For months, the US departments of Energy, Treasury and Homeland Security, among others, have briefed big electric utilities and banks on Russian hacking capabilities, and urged businesses to lower their thresholds for reporting suspicious activity.”

Some companies aren’t prepared

The bottom line of Biden’s warning Monday and the FBI advisory was that the infrastructure behind US society and American life is mostly in private hands and that it needs to be made more secure from hacks.

Anybody who remembers the ransomware attacks on the major US food manufacturer JBS, US cities, an oil pipeline and hospital systems in recent years knows this to be true.

Biden has told Putin to cut it out

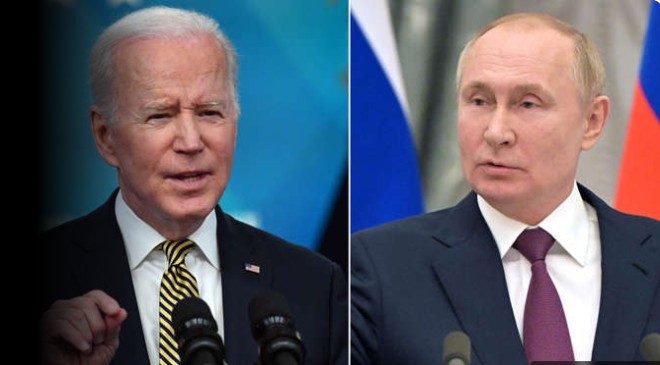

Biden has warned Russian President Vladimir Putin not to use cyberattacks against the US. The President on Monday referred to the conversations as an “altar call.”

“We’ve had a long conversation about, if he uses it, what would be the consequence,” Biden told business leaders on Monday.

Biden has more control over that consequence than he does over the preparedness of US companies that are involved in American infrastructure. He appealed to their sense of “patriotic obligation” to get their cyber-defense capabilities up to scratch.

He specifically mentioned the energy, power and financial sectors.

What might a large-scale cyberattack look like?

It’s happened before. Estonia was the victim of a large-scale cyberattack in 2007, although there was not enough evidence to definitively pin it on Russia at the time.

CNN’s Ivana Kottasová wrote about the attack, which Estonia considered an act of cyber-warfare, last June. It all started with Estonia’s decision to remove a Soviet-era war memorial from central Tallinn.

Here are some key lines from her report:

The attack made Estonia realize that it needed to start treating cyber threats in the same way as physical attacks.

At that time, the country was already a leader in e-government, having introduced services like online voting and digital signatures. While no data was stolen during the incident, the websites of banks, the media and some government services were targeted with distributed denial of service attacks that lasted for 22 days. Some services were disrupted, while others were taken down completely.

NATO and the international community took notice of the attack on Estonia and experts developed a standard to assess cyber-war as a result.

When is a cyberattack an act of war?

I called Tess Bridgeman, co-editor in chief of the website Just Security and a former attorney in the Obama White House who is an expert on war powers and international law.

“If a cyberattack causes significant death, destruction or injury, of the same sort that you would see from a more traditional attack using kinetic means, like bullets or missiles, you know, then you would call it a ‘use of force’ in international law,” she said.

A cyberattack that targeted a dam or air traffic control towers might rise to this level, but the government would try very hard to avoid responding to a cyberattack with a military attack, she said.

The attacks on the US to date have fallen short of the threshold to justify a military response.

As the government seeks countermeasures to respond, Bridgeman said, there’s a good chance they won’t be publicly known.

“It may appear that the US is sitting by idly, but I would be highly doubtful that that’s the case,” she said, arguing that defensive actions might be more effective at de-escalating the standoff. “It’s setting the example for what responsible state behavior looks like.”

Could weapons be used to respond to a cyberattack?

The threat of a military response is always there for the worst cyberattacks, should they cost American lives.

“Our policy, our declared policy is, if it’s a big enough attack on us and it hurts us, we will use the conventional weapons response,” Richard Clarke, who was a top adviser to President George W. Bush on cybersecurity, told CNN’s Michael Smerconish shortly after the war in Ukraine began.

“So we could very easily find ourselves in a shooting war with Russia if they try devastating — and that would have to be devastating — cyberattacks like turning out the power grid,” Clarke said.

Most of these attacks are meant to be part of espionage campaigns or to be meddlesome rather than deadly. Clarke argued that Russian attacks on US industries could be more devastating than attacks on the government itself. He said the government doesn’t really know what would happen if the Amazon, Google and Microsoft cloud systems went offline, for instance.

“I can tell you if those clouds go down, the United States stops working, our economy stops working, the phones stop working — we will find ourselves pretty soon in the dark ages if the internet goes down,” said Clarke.

What if Russia attacked a US ally?

It’s not clear that Russia would want to provoke the US specifically in a such a devastating way, or how the US would respond.

While its cyberattacks in Ukraine since the war began have been less severe than some expected, according to a report by Lyngass, Russia has targeted internet infrastructure in parts of the country.

There has been concern that cyberattacks in Ukraine could spill over to nearby countries that are in NATO and could lead the organization to invoke Article 5 of its charter — the principle that an attack on one member of NATO is an attack on all members.

Could a cyberattack trigger Article 5?

A cyberattack could absolutely trigger Article 5. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg made this clear in February just after Russia’s invasion.

“An attack on one will be regarded as an attack on all,” Stoltenberg said at a news conference when asked about a potential Russian cyberattack.

But he added that NATO would be very careful in assessing an attack and would make sure a cyberattack on Ukraine — shutting off electricity, say — that accidentally spilled over into Poland or Romania is not construed as an attack on those countries.

He also said it’s intentionally unclear what kind of cyberattack would rise to the level of invoking Article 5.

NATO, he said, would not want to “give a potential adversary the privilege of defining exactly when we trigger Article 5.”