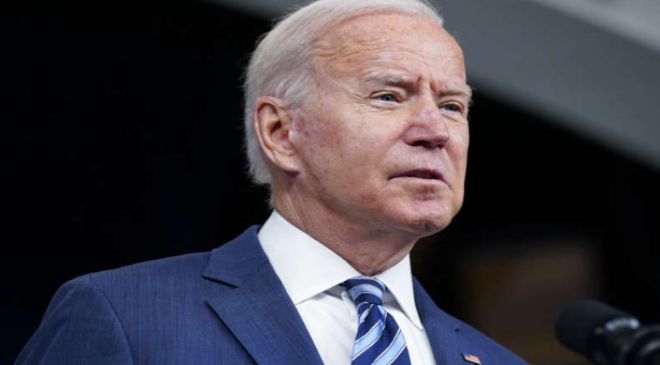

Joe Biden always says foreign relations is about relationships, and he’s been developing the one he has with Vladimir Putin for two decades.

Biden warned that Putin had dreams of rebuilding an authoritarian empire going all the way back to his days as a senator from Delaware. On the campaign trail, he said repeatedly that he knew Putin didn’t want him to win.

Since the beginning of his time as President, Biden has relied on his sense of the Russian leader to guide his own response. It’s even guided the way Biden deals with Putin in their conversations, repeatedly interrupting what he and aides see as the Russian President’s strategy of going off on tangents meant to muddle and undermine.

According to a dozen interviews with White House officials, members of Congress and others involved in the effort, Biden has deliberately worked with allies abroad to deny the Russian leader the one-on-one, Washington vs. Moscow dynamic that the President and his aides think Putin wants. Publicly and privately talking about the war as a fight for freedom and democracy, Biden has left other leaders to speak with Putin.

He has moved just as deliberately at home to depoliticize opposition to the invasion of Ukraine so that, even among Republicans, support for Putin has been forced to the fringes so that vilifying the Russian leader has become the one major area of bipartisan agreement since Biden took office. This week Biden ratcheted up his rhetoric by calling the Russian President a “war criminal,” a “murderous dictator” and a “pure thug.”

“What Putin is trying to do is surround and encircle Kyiv,” said Rep. Greg Meeks, a Democrat who is chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. “What Biden is trying to do is have the whole world surround Putin.”

Part of the lesson Biden took from being involved as vice president during Putin’s 2014 invasion of Crimea was that NATO nations would need a much faster, more humiliating and more cohesive response than the months of infighting that produced sanctions so weak that Putin rode them out. Yet administration officials admit privately that if Putin had invaded Ukraine a year ago, events might have unfolded much differently coming right off four years of former President Donald Trump’s damaging relationships and calling NATO obsolete.

Campaigning in 2020, Biden spoke about the confrontation he saw coming.

“Putin has one overriding objective: To break NATO, to weaken the Western alliance and to further diminish our ability to compete in the Pacific by working out something with China,” Biden told CNN’s Gloria Borger at the time. “And it’s not going to happen on my watch.”

Biden’s own last conversation with Putin was on February 12, more than a week before the invasion started. And for a President and aides who on almost everything else complain that they don’t get the credit they deserve, on Ukraine he and administration officials have ducked talk about him being leader of the free world, despite how much of the sanctions and international response are a result of Washington’s guidance and pressure.

The result is Putin’s being boxed in more than even Biden had expected, along with a sustained level of attention to the war abroad and in America that has surprised White House aides — without rebooting a 1980s-style Cold War.

“Joe Biden,” a senior administration official said, “has known Vladimir Putin for decades and knows exactly who he’s dealing with.”

Cutting Putin off — literally and figuratively

Cutting off Putin began, as Biden might say, literally.

Whenever they’d speak, Biden would interrupt Putin as the Russian President launched into complaints that American officials see as a whataboutism tactic designed to distract and undermine.

No, Biden would say, that’s not what we’re talking about, according to one senior administration official who has witnessed those conversations. Or, no, that’s not how things happened 20 or 25 years ago, in whichever past grievance Putin was bringing up to justify his behavior.

“President Putin can’t use a lot of his common tricks with President Biden, like trying to confuse people by going down long historical tangents or meandering into the minutiae of policies because President Biden sees those tactics coming a mile away and doesn’t take the bait. He’ll try to get President Biden off topic by citing an obscure section of the Minsk agreements or a speech someone gave in the late 1990s,” a senior administration official said, adding that Biden “is going to always steer the conversation directly back to what he’s come to talk about.”

Biden has often told a story of a meeting with Putin at the Kremlin in 2011, when he was vice president, and telling the Russian leader, “I’m looking in your eyes and don’t think you have a soul” — a cutting response to President George W. Bush’s infamous 2001 comments getting a sense of Putin’s soul from looking him in the eye and finding him to be “very straightforward and trustworthy.” A Biden administration official, by contrast, sent CNN highlights of Biden’s history on the topic over the years, from calling Putin a “bully” in 2006 to calling him a “kleptomaniac” in 2019.

A White House aide who was in the Situation Room for a rushed National Security Council meeting on February 10 said Biden’s sense of Putin was on display throughout how he ran the conversation in which the White House’s assessment of an invasion moved from a possibility to an almost certainty.

“He was clear and clear eyed in that meeting that he believed that Putin would do this,” the aide said. “He spoke with the experience of somebody who knows Putin and has dealt with Putin.”

Biden learns from 2014 and the importance of unity

Biden thinks he wouldn’t be able to keep the current levels of unity — in the US and around the world — if Putin sparked the kind of partisan breakdown that he did in 2014, when many top Republicans spoke admiringly of his strength and leadership largely because he was taking on Barack Obama.

Biden hasn’t — as some in his party want — gone after Trump, brought up the attack on the 2016 elections or attacked Republicans for voting against the former President’s first impeachment when Trump leveraged withholding military aid to Ukraine — in pursuit of dirt on Biden.

“The crisis in Ukraine is clarifying what was at stake back then, and there should be accountability for that,” said Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney, the chair of the House Democrats’ campaign arm. “I don’t think it makes sense to play politics with a war. I think it makes sense to be a moral voice for what’s right and what’s wrong — and I’m proud that I belong to a party, and we have a president, who knows the good guys and the bad guys in Ukraine. And the other side seems to be struggling with that.”

That message won’t be coming from the President himself.

Putin wanted to divide us. We’ve been united. It’s important that we send that signal to the world,” the White House aide said.

Most Republicans — with a few notable outliers, including Trump’s own clear struggle to try to erase the memory that his first response to the invasion was calling Putin “smart” and “savvy” — have not gone on the attack against Biden, despite many differences among Republicans and Democrats alike about particulars of the President’s response.

Republicans have not, though, been convinced on the other part of Biden’s strategy: Calling rising fuel costs “Putin’s price hike” and “Putin’s gas tax” as an attempt to assuage voters.

“These are not Putin gas prices. They are President Biden gas prices,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy said last week.

On Tuesday, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell added, “It’s pretty clear that Vladimir Putin is not the cause of this rampant inflation.”

White House aides are tracking all the Republicans in the House and Senate who are calling for tougher energy sanctions on Russia — preparing to try to undermine them as hypocrites if they complain about higher gas prices on the campaign trail this fall. But at the same time, Biden himself has kept up outreach to Republican lawmakers.

That’s included personally briefing all four top congressional leaders together last month and surprising a bipartisan delegation to the Munich Security Conference with a call to thank them for their support. During that call, Vice President Kamala Harris held her cellphone to a microphone so the lawmakers could hear Biden speaking from behind the desk in the Oval Office.

Putin has been tracking what Biden has been doing and saying about him for years. That includes friendly Russian commentators complaining in 2009 that Biden was a “gray cardinal” secretly orchestrating a tough Obama administration response to Putin’s leadership after the then-vice president said Russia was limping along, or a Kremlin spokesman on Thursday saying that Biden’s war criminal remark was “unacceptable and unforgivable.”

Even as Biden has ramped up what he’s been saying about Putin, there’s only so far he can go before tripping into the escalation he’s so desperately trying to avoid.

“It hurts him to see the devastation in Ukraine, and it would be easy to say, ‘That guy’s evil and we’re going after him and we’re going to get him,'” Meeks said. “The question is: Is that the right thing? Because then you’re talking about World War III.”